According to a Chinese saying there are seven necessities for everyday life: firewood, rice, oil, salt, sauce, vinegar and tea. There are also seven things that are considered graceful to do for those that lead a noble life: zither, chess, calligraphy, painting, poetry, wine and tea. Tea is the only thing in Chinese culture that can be as simple and common as a little component of daily life, at the same time, it can be as sophisticated and elegant as a piece of art. Just as it takes more than just time to form a culture, it requires more than using gaiwan to understand Chinese tea culture. In the series of The Art of Chinese Tea, I will dive into the historical, cultural, and technical areas of Chinese tea, and share with you more profound aspects of Chinese tea.

It may seem a bit simplistic to talk about how Chinese tea lovers taste tea. Isn’t it obvious? Drink and describe, simply speaking. As for how to describe the tea, it becomes more subjective. What you taste is what you taste. There are even flavor profile wheels that help people describe tea better. But is that all? Absolutely not. When tasting fine teas, more is required than just the palate. Real fine tea tasting is reading all of the abundant information a leaf presents to you. Have you ever hear of tea masters in China who can tell what the weather was on the day that the tea was made by simply having a sip? Is it just a story? You might have some idea after reading this article.

Reading the dry leaves

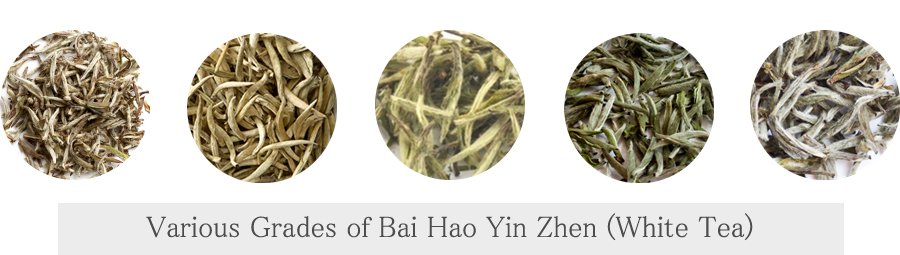

To appraise the tea, the appreciation starts before it is brewed. The uniformity, the shape, the color and luster, and the aroma all contribute to the quality of a tea. First we observe if the tea leaves are uniform. Is there anything other than leaves mixed in the tea? Is size of the tea leaves consistent? This tells you how carefully handled the tea was and whether the tea is mixed with other grades or not which is of great importance when it comes to fine tea buying. During the green tea buying season in the spring, the price of the teas change on a daily basis. When examining the look of the dry tea leaves, the priority is to see if it matches the tea name. As mentioned in earlier articles, Chinese tea names have become a standard and there are certain requirements that must be met in order to hold a prestigious name. For example, if it’s Bai Hao Yin Zhen (white tea), it has to be made entirely of buds. If it’s Tai Ping Hou Kui (green tea), the individual leaf has to be big and flat, wider in the middle and pointy on both ends with clear veins running through the whole leaf. The color and luster of the tea leaves is another important factor in appraising the tea. The lightness or darkness of the dry leaves tells us the state of freshness of the tea if it’s green tea or the oxidization and roasting level of the tea if it’s oolong. Color plays an important part in naming and grading as well – does the color matches how the tea is supposed to be? Long Jing (green tea) should have a yellowish green color while Liu An Gua Pian (green tea) is deep green. Lapsang Souchong (black tea) has a lustrous dark color while Dian Hong has some of gold tips among the dark leaves. As for aroma, smelling the dry leaves will point out the general aroma profile of a tea, but at the same time, you can also find out if the tea is stored properly. Is the smell of the tea mixed with other smell or does the tea seem to smell as if it’s going bad?

From scrutinizing the dry leaves of the teas. There is some general information you can retrieve: the category a tea belongs to, was the tea processed with care, how the tea was processed, the season the tea was picked, the oxidization level, was the tea stored properly, and most importantly, is this actually the tea you are being told that it is. These initial messages together with the later tasting experience will give you a full picture of this tea. With some water, a vivid picture of the life of the tea unfolds in front of you, from its growing time to how it’s processed. The story of the tea doesn’t need someone else to narrate. A tea leaf quietly reveals to you its story. But are you able to listen carefully do you have the key to read it?

No matter how good a tea looks, the ultimate factor of evaluating its quality is the actual tasting part. In the next article, I’ll explain how to taste fine tea. The depth and the breadth is more than simply naming the flavours.

Tasting the liquor

With a cup of freshly brewed tea in hand, start by looking at the tea again, but this time observe the brewed liquor of the tea. What color is it? White teas might be pale green or pale yellow. Black teas are mostly maroon. Is the liquor clear or cloudy? For green tea, sometimes a slightly cloudy liquor is actually good news as it reflects the abundant essence of the tea, while for teas like oolong or dark teas, it shows a deficiency in the process.

Smell the liquor while it’s still hot. It will make any odor more obvious compared to the dry leaves. During the tasting, the experience on nose is as crucial as the mouth. The warm/slightly hot liquor releases the truth aroma of the tea. When the drink is finished, don’t forget to smell the empty cup. A lukewarm cup with a lingering fragrance gently speaks to the quality of the material (the raw leaves). You are very likely to find that the aroma from a high mountain tea endures much longer than those grown on plains.

The first sip of the tea not only tells you about the tea, but also demonstrates how the tea is brewed (if not cupping). Reading the dry leaves of the tea helps to reveal the proper way of brewing a tea, and in the first steep, you might find the tea is over, or under brewed, that the water temperature wasn’t quite right, or that the brewing method didn’t provoke the full aroma from the tea.

Then, a little sip of tea, don’t rush to swallow it, let the liquor imperceptibly glide down the throat. Taste the flavour of the tea. Among the basic tastes, is the liquor a bit sweet, or bitter? A lot of the times, the bitterness of the tea is caused by improper brewing, but certain teas such as Zhu Ye Qing (green tea) does have a subtle of bitter edge. As for the flavours of the tea, with sufficient food experience a tasting profile wheels can help a lot. The soybean flavour of Gu Zhu Zi Sun (green tea), the apricot note of Bai Hao Yin Zhen (white tea), the dark chocolate taste of Da Hong Pao (oolong tea), the camphor savour of aged Pu’er (dark tea), you name it. Beside the flavour, what is the texture of the tea? What does your tongue feel after the tea, is it smooth, moisturized, and nourished, or is it astringent or even dryer than before? Do you feel the hint of tartness on both sides of the root of your tongue? Do you have a bit of sweetness creeping back to you mouth after the tea? Do you have the aroma of the tea lingering in your mouth and nose?

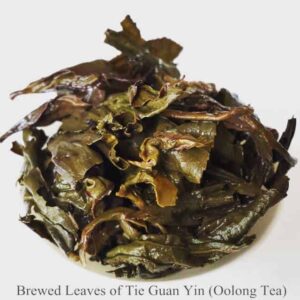

Moreover, take some time to examine the brewed leaves. The fully opened leaves make it easier to see their situation compared to the dry leaves. Are they all buds as they are supposed to be? When were the leaves harvested? How is the oolong bruised/oxidized? Is the Pu’er really made of old trees or big leaves as you were told? Observe the shape of the leaves, look at the portion between the leaves and the stems, touch the leaves, and you will find the answers to these questions.

Feel the tea

Besides the flavour and aroma elements that are revealed during the tasting, what else do you need in order to describe a tea? The personality of the tea. It may sound absurd, but when it comes to appraising fine teas, it is the personality of the tea that elevates one tea to a better grade than its peer. Is the aroma light-weighted and quick to diffuse, or mature and sturdy? Is the taste superficial, flimsy, and plain, or is it complex, sophisticated, and multidimensional? A good tea is like an elegant gentleman or lady: mature, steadfast and never boring. It’s consistent with subtle changes and nuances emerging through the infusions. Tasting a fine tea is also similar to reading a masterpiece. It requires experience and heart to understand every detail.

A tea leaf will tell you everything you want to know about it. But are you able to understand it? To be a good tea taster and a true sommelier requires intensive understanding of tea, both knowledge and experience. As the saying goes: taste, live and learn.

One Reply to “The Art of Chinese Tea: Fine Tea Tasting”